- Home

- Anna Stothard

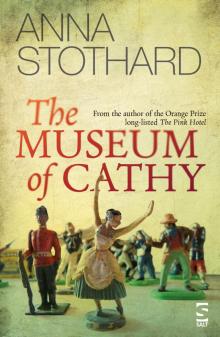

The Museum of Cathy

The Museum of Cathy Read online

THE MUSEUM OF CATHY

Anna Stothard

From the author of the Orange Prize long-listed, The Pink Hotel

Cathy is a young woman who escapes her feral childhood in a rundown chalet on the East coast of England to become a curator of natural history in Berlin. Although seemingly liberated from her destructive past, she commemorates her most significant memories and love affairs – one savage, one innocent, one full of potential – in a collection of objects that form a bizarre museum of her life. When an old lover turns up at a masked party at Berlin’s natural history museum and events take a terrifying turn, Cathy must confront their shared secrets in order to protect her future. This is an exquisitely crafted, rare and original work.

Praise for The Art of Leaving

“Stothard gets her talons into you . . . read it for its beguiling heroine and sparky prose.” Sebastian Shakespeare, Tatler

“Anna Stothard’s third book, after the much-praised Isabel and Rocco and The Pink Hotel, confirms her talent: the prose here can be transfixingly good,” The Independent

“A stunningly accurate and chilling account of the acquiring of emotional wisdom, with vividly drawn characters,” Kate Saunders, The Times

“A witty, beguiling and increasingly poignant novel about the scars – physical and psychological – that make us who we are.” Stephanie Cross, The Lady

“I would recommend it to anyone who likes being told a very good story,” NewBooks

“Anna Stothard’s third novel cements her place as one of Britain’s best young authors . . . Stothard’s lush, dreamy prose is given full rein . . .” Kaite Welsh, The Literary Review

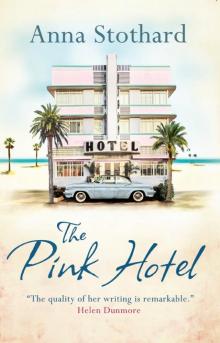

Praise for The Pink Hotel

“Astonishingly good . . . Stothard’s writing is accomplished and very engaging.” Kate Saunders, The Times

“Matters of personal identity underlie an exhilarating ride through LA’s seamier side in the company of a hard-bitten yet highly engaging protagonist.” Ross Gilfillan, Daily Mail

“An elegant noirish mystery.” Amanda Craig, The Independent

“A gently transgressive, transatlantic quest that conjures up both the languid heat of LA and the confusions of a young woman on the cusp.” The Lady

“Anna Stothard’s descriptions are almost like a painting – the reader finds themselves slap bang in the middle of the America that is rarely shown in film or novels.” Anne Cater, NewBooks

“Anna Stothard’s dark debut Isabel and Rocco, written while the author was still at school, was a McEwan-esque tale about two teenage siblings left to fend for themselves. Her second novel, set amongst the naval-gazers of California, proves no less precocious.” Emma Hagestadt, The Independent

“A beautiful book.” Anna Paquin, RED magazine

Praise for Isabel and Rocco

“Anna Stothard’s pre-university debut is dazzling . . . surly and oversexed, vulnerable and murderous . . . it is remarkably accomplished” Geraldine Bedell, The Observer Review

“Stothard’s claustrophobic and compelling atmosphere of sadistic sexual fizz between her two main characters keeps the reader gripped” The Times

“Sinister debut from an author who shows serious promise. The plot has echoes of Ian McEwan’s The Cement Garden – two children mysteriously left alone by their parents.” Jo Craven, Vogue

“Rainy streets, kindly but inept teachers, rotting food and the highly seductive, just-surfacing, notions of forbidden sex – Stothard describes them all brilliantly” Carolyn Hart, Juice Magazine

“A dark tale of enfants terribles set in North London, Isabel and Rocco revolves around a brother and sister with an unhealthily obsessive relationship” Marianne Brace, Harpers & Queen

“With shades of Lord of the Flies, Stothard has produced a chilling and haunting work” Annabel Venning, Daily Mail

The Museum of Cathy

ANNA STOTHARD is the author of three critically acclaimed novels, published all over the world. She has been longlisted for the Orange Prize for Fiction and her third novel, The Pink Hotel, is being made into a film by Anna Paquin. She currently lives in London after spending two years in Berlin.

ALSO BY ANNA STOTHARD

Isabel and Rocco (2003)

The Pink Hotel (2011)

The Art of Leaving (2013)

Published by Salt Publishing Ltd

12 Norwich Road, Cromer, Norfolk NR27 0AX

All rights reserved

Copyright © Anna Stothard, 2016

The right of Anna Stothard to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Salt Publishing.

Salt Publishing 2016

Created by Salt Publishing Ltd

This book is sold subject to the conditions that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

ISBN 978-1-78463-083-6 electronic

To Sally Emerson

The Museum of Cathy

An elephant skull and a swallow rested on a cabinet of moths, all specimens of natural history that didn’t have a place in the museum downstairs. The bird was particularly beautiful, three inches tall, with an ochre neck tapering down into forked blue wings. It had glossy black eyes that Cathy could have sworn just blinked at her.

A few corridors over, a gallery the size of a tennis court contained thousands more stuffed birds so if this one was magically twitching back to life perhaps the matronly pelicans were also preening, the flamingos stretching their legs, the penguins sneezing and the two hundred hummingbirds rustling their feathers ready to seek revenge for the decades in which they’d been prodded and observed. Cathy smiled at the thought and then caught her breath when the swallow chirped twice, its feathered throat vibrating: it was not a specimen, after all. It looped down from the shelf and sailed past a cabinet of dragonflies to land on a pile of science journals.

Cathy was not easily spooked. She would walk first into fairground haunted houses and swear on people’s lives without blinking, yet as the swallow looked for an escape route her hands were shaking. Trapped birds, her mother would say, were a warning.

“He likes you,” Tom said from the doorway. She didn’t immediately turn towards him, instead reaching over a desk to open the window for the swallow. A low hum of jazz music and laughter lifted up from a party in the museum’s public galleries two floors below.

“He’s not in a position to be choosy.” Her face was still tilted away from Tom as he stepped into the room. The bird remained poised and stared directly at Cathy from its shelf. Tom adjusted his glasses and did the same. She looked new but familiar in her green silk evening dress, as if she’d discarded a layer of herself and climbed out raw. Her hands were shaking and when she eventually shifted her face in Tom’s direction she revealed a bruise forming on her eye and a little blood on her mouth.

The swallow darted off across the room again, making them both flinch, still not heading for the window but soaring down from the table to a cabinet full of Monarch butterflies, where it shat a pool of white that dribbled down the glass.

The creature flapped its wings while treading air, its body curled into the shape of a comma. Cathy’

s skin had a feverish sheen to it. She licked a droplet of blood off her top lip with her tongue.

“Are you going to tell me what happened to you tonight?” said Tom. “I’ve missed you.”

A Kissing Beetle

The past is not stable. The act of remembering changes us, and our whole lives can be re-written in a day. First thing the morning before the party she had paused in the doorway of the Berlin Natural History Museum and smiled good morning to a Brachiosaurus skeleton, his long neck skimming up to the atrium’s glass ceiling. Cathy’s dress for the evening’s party was already dry-cleaned and hanging up at work but she carried high heels past fossils and polar bears across the marble floor.

It was going to be another humid day. Botanists, technicians and research fellows plodded through the museum while a cleaner dusted a glass case of dodo bones. Cathy turned left from the atrium into the darkness of a solar system exhibition with nine football-sized planets around a sun that was, misleadingly, exactly the same size as the planets. A day on Venus takes 243 earth days, a poster said. Jupiter takes 9.8 hours. Teenagers in particular congregated excitedly at the bottom of these stairs every day to kiss in the darkness. Cathy liked to imagine the teenagers aroused by the idea of their entire universe once being contained in a single, unimaginably hot point in space, but they probably just liked sneaking off into the dark.

Cathy wore a white shirt, tailored trousers and ballet slippers, her long auburn hair tucked neatly behind both ears. She twisted a coiled snake engagement ring on her left ring finger as she paced up a curved staircase towards the locked doors of various laboratories and collection rooms. Gallery and corridor windows were flung open in this uncanny summer heat, trying to dilute the smells of hot fur and preservation chemicals. She pushed into her office, a long room with a low ceiling cluttered with furniture and an ever-changing array of specimens that did not fit downstairs. Semi-broken office chairs were piled in the same corner as a stuffed owl while an elephant skull was perched on one of the many green cabinets arranged around the room, packed with everything from Atlas Moths the size of a baby’s head to Pigmy Moths smaller than a comma in this sentence.

She sat down at her desk in front of the cedar wood tray of Deathshead Hawkmoths with orange underwings and skull shapes on their abdomens, bad omens throughout time. Cathy loved her rows of tidy pinned bodies with their fragile costumes, but she was equally besotted with the empty spaces in between each specimen. It was in these gaps that order existed. She believed the beauty of museums, like maps and human relationships, was in distance as much as connection.

She’d woken up next to Tom that morning and left him sleeping in their one bedroom flat with white floorboards in the south-eastern part of Berlin, Neukölln, an area full of battered launderettes and Turkish cafés where they’d lived for the last four years. She was English and Tom was American, part of the tapestry of exiles and drifters that made up the city. When Tom was asleep he looked like some evolutionarily superior species with his white teeth, square jaw and tanned face, his thin eyebrows giving him a perpetually amused expression. The moment he woke up he would start fiddling with his often-broken spectacles, shifting his weight from foot to foot and chain smoking, but asleep he was pristine. The flat had the empty atmosphere of a holiday cottage. The centrepiece was a wrought iron bed that was more of a disorderly pet because it made such a noise. Tom slept without moving but Cathy conducted nightly conversations with it. The frame groaned when she stretched, the mattress squeaked when she wriggled. Sex was a threesome, with the bed the most vocal participant. It seemed to mock them when they got off rhythm. They’d roll onto the floor but it still felt as if the bed were collaborating somehow.

As she sat down at her desk she saw a cardboard box about the size of her hand in the far corner, next to a microscope. The brown package must have come in early this morning or after she’d left work last night. She was glad that there was no one else in the room just then, or she was sure her colleagues would have been disturbed by the sound of her heartbeat.

Cathy slid the package nervously towards her body. She had published two journal articles on hawkmoths, so people did occasionally send specimens for her to identify or add to the museum’s collection, but instinctively she knew the brown box wouldn’t contain a moth. Her hands shook. Saliva filled her mouth. She slit the duct tape lengthways and twice horizontally with the end of a pair of scissors, opening the flaps to disclose polystyrene. She reached her right hand in to find a white box, nudging the lid off with her thumb: something padded in newspaper.

She unwrapped the layers to reveal a one-inch nugget of luminous amber that felt cool between her thumb and forefinger. She held it up to the light. Inside the amber sat a Panstrongylus megistus, a Kissing Beetle, its slender head suffocated in resin. One antenna appeared to twitch as if reacting to Cathy’s warm skin. Timeless creatures, shiny bullets of time, they were called Kissing Beetles because their habit was to bite sleeping humans in the soft tissue around the lips and the eyes. There was no label or letter of explanation, but she knew who this message was from.

Daniel clenched and stretched his fingers, chlorinated water slicking down wrist hairs under the cuff of his hotel dressing gown. He had arthritis and enjoyed swimming more than fighting now, yet when he looked at his hands he thought fondly of hushed air and the sting of glove-burned flesh. A first punch that hit the ridge of his opponent’s cheek, the sound of split bone but no time to be pleased about it. He ran fingers through his damp hair.

On the table was a fossilised sea eagle claw, an inch of chocolate brown bone neatly attached to a shard of finger. The claw had a little restoration at its tip but was otherwise immaculate. Cathy had told him once that a mouse’s forelimb, a whale’s flipper, a bat’s wing and a human arm share almost the same pattern of bones. His own gnarly hands were as much ancestors of the raptor as a bat’s wing.

Daniel’s throbbing knuckles gave him a sense of unease. He was probably anticipating the breaking of the city’s heat wave, maybe a storm after days of humidity. He was not used to this new freedom available to him, the knowledge that he could move around as he pleased. He touched the tip of the claw with his forefinger and thought of Cathy’s lithe and bony hands with a seashell ring at the base of her middle finger. For a decorative fuck you, she’d once said.

Cathy unfolded the newspaper pages that the Kissing Beetle had been wrapped in and studied them. It was yesterday’s copy of the German newspaper Die Welt, with half an article on how motorway tarmac was buckling near Abensberg in Lower Bavaria because of the heat. A school bus had hit a crash barrier, killing twelve children. In the torn left corner of the page, pasted on top of the newsprint, was a fragment of a sticker that said:

ments of

Shiro,

eakfast!

Cathy lifted this bit of information to get a closer look at the words. A complimentary newspaper with breakfast. There was a chain of hotels called Shiro; several were in Berlin. The hairs on her neck stood on end. There was no postmark on the cardboard box, but she ran her fingers across the deep grooves he’d made while writing her name on the top. It had been four years since Daniel had sent her an object like this. The palms of her hands were sweating.

Windows were open around the room, but none appeared to let in much of a breeze. Her office was right at the top of the museum, looking out on the front lawn. Peaking up above hotels and blocks of flats to her left, she could just see Berlin’s TV tower glinting like a giant disco ball in the sky. Most of Berlin’s old museums were trapped on their own island in the city centre, but the Natural History Museum was a lone wolf up near the university and the central train station. It was a long building with a flat roof, the façade decorated with arched windows and pollution-grey sculptures that hid a puzzle of old and newly renovated wings behind. She could hear tourists and children outside the window, plus the chants of protesters who had been lingering on the front lawn re

cently, objecting to the museum’s acceptance of sponsorship from an oil company. Inside the office there was just a focused hush of curators bent over trays of ladybugs or computer keyboards. She closed her eyes and moth wing-patterns, colourful circles and zigzags, danced on the back of her eyelids.

Cathy removed a little brass key from the pages of her Encyclopaedia of Insects on the shelf and slipped it into the cedar wood doors of a cabinet underneath her desk. This department of the museum had been modernised a few years ago and most of the antique storage units had either been sold off or warehoused to make way for the green steel that currently filled the office. Cathy had saved one old cabinet for herself, four feet wide and two feet tall with a splintered crack down its panelled double doors. She kept it underneath her desk, but it had never contained the articles on phylogeny, biogeography or wing polymorphism advertised on the labels.

The doors creaked open and Cathy paused to make sure her colleagues were all busy pinning wings or dissecting abdomens, making tiny cuts between heart pulses in their own thumbs. One of the many things she loved about working in natural history museums was that she would never be the only person with strange archiving habits. There was a man in the whale storeroom who had a drawer marked ‘string too small for further use’.

The Pink Hotel

The Pink Hotel The Museum of Cathy

The Museum of Cathy